Barnabas - sicut scriptum est - Latin interpolation?

This was controversial, would Barnabas be quoting Matthew?

What does other earlier Greek Barnabas say, papyri ?

The Origen of the Gospels - 1866

Mombert

https://books.google.com/books?id=eF8QAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA558

p. 558

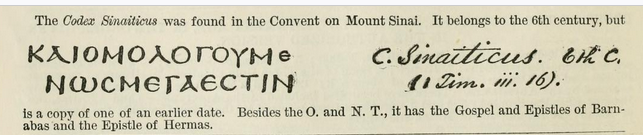

The recent discovery of the Codex Sinaiticus by Tischendorf furnishes additional and incidental testimony for the existence of the evangelical canon at the beginning of the second century. That famous and most ancient manuscript on parchment extant, contains the entire Greek text of the Epistle of Barnabas, the first five chapters of which were, until that discovery took place, only known from an old Latin Codex. In that Latin text, occurs the following passage at the end of chap. iv:

"Adtendamus ergo ne forte, sicut scriptum est, multi vocati, pauci electi inveniamur." The words sicut scriptum est were regarded as

the interpolation of a Latin translator, but the original Greek text in the Codex Sinaiticus has the passage from Matthew with the introductory words," as it is written "; and this vindication of the Latin text of an Epistle which cannot have been composed later than the beginning of the second century, yields the important result that its author cited the first canonical Gospel as scripture, for this formula was used to distinguish holy writ from other writings (cf. Matt. iv. 1, etc., Luke iv. 1, etc.), and that consequently at that carly date the Gospel of Matthew had canonical authority.

p. 561

These results are as follows; there is no doubt that the earliest Latin version of the Gospels was made soon after the middle of the second century, for the Latin translator of Irenaeus (just before the close of that century) and Tertullian (during the last decade of that century) wrote in undeniable dependence on that text. That earliest version,1 at least in its main features, is still extant; 2" for our oldest documents for that text emanating from North Africa, the home of Tertullian, receive for many of their readings the confirmation of two ancient witnesses (Irenaeus and Tertullian), so that even those sections of the text which are not found in their writings, must be supposed to agree with, or at least come very near to, that oldest redaction. But

the discovery of the Codex Sinaiticus carries us much further, for the Sinaitic text, which competent scholars on paleographical grounds pronounce to have been written in the middle of the third century, exhibits so

striking an affinity with the oldest Latin version, that it must be considered to be in essential agreement with that text from which the first Latin translator, the originator of the so-called Itala, made his translation; and that this text was not of an isolated character is evident from the agreement with it of the recently discovcred most ancient Syriac text of the Nitrian MS. of the beginning of the fifth century, of Origen, and others of the earliest Fathers. This Syriac text is analogous with the Itala in the twofold proof to be noticed forthwith, for the most

p. 561

But we have still a far more important result of textual criticism, which in the opinion of Tischendorf affords evidence that all our Gospels have to be brought down to the beginning of the second, if not to the end of the first, century.

"For while

on the one hand the text of the Sinaitic MSS., as well as the oldest Itala text, belong to the use of the second century, it is on the other hand by no means difficult to prove that the same text-its superiority over other documents notwithstanding-has in many respects

departed from original purity, and presupposes an entire text-history. Here we are not exclusively limited to the Codex Sinaiticus, this or that MS. of the Itala, with Irenaeus and Tertullian, but we may include all those text-vouchers which in part are necessarily, and in part most probably, to be traced back to the second century, and reach the result of the undeniable fact that a rich text-history lies already back of it. We mean to say that even before the second half of the second century, when repeated copies of our Gospels were made, not only many mistakes of transcribers took place, but that sometimes also the expression and sense of single passages were changed, and sometimes greater or smaller additions from apocryphal or oral sources were made, not excluding even those changes which testify in particular for the early collection of our Gospels into a canon and originated in the collocation of single parallel passages. If this is really the case, if an important stage of the text-history of our four Gospels lies really before the middle of the second century, before the time when canonical authority and the more firmly established ecclesiastical order cast up an ever-growing dam against arbitrary modifications of the sacred text (and we engage to furnish elsewhere full proofs on his head), we have to claim at least half a century for this history. Are we therefore not constrained to fix the beginning, for we dare not say the origin, of the evangelical canon at the end of the first century? and does not this result grow more certain from the fact that all the historical factors of the second century, which we have produced without holding anything back, have been formed to agree with it" (Tischendorf, 1. c. pp. 66, 67)?

=====================================

Example of controversy

The Four Gospels Examined and Vindicated on Catholic Principles (1863)

Michael Heiss

https://books.google.com/books?id=mQReAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA22

So much however is (even by the adversaries) admitted that this epistle was written early in the second century.†) Now in this epistle we read: "Adtendamus ergo, ne forte, sicut scriptum est, multi vocati, pauci electi inveniamur." Let us be attentive to ourselves, lest perhaps we may be found (wanting) as it is written, many are calledfew chosen. This sentence "multi vocati, pauci electi," is nowhere found in Scripture, except twice in the gospel of St. Matthew, namely: chap. 20, 16, and chap. 22, 14. Hence it is evident that the author of this epistle has known the gospel of St. Matthew. Yet the hypercritics of our time, as Credner and others, objected to the conclusions drawn from this quotation, that the words "sicut scriptum est," as it is written, are merely the gloss of a copyist, and therefore not genuine; the sentence "multi vocati, pauci electi," as other sentences of Christ in the writings of the apostolic age, has not been derived from a written document, but from oral tradition. It was difficult to refute this objection, as we had not any longer the Greek text of this passage of the epistle, but only a latin translation. But lately the learned Tischendorf, a protestant, has discovered a most remarkable codex of the Bible in the convent of St. Catharine, on the mount Sinai, in which also the Epistle of St. Barnabas is contained in the Greek original, the disputed words "sicut scriptum est" are found in the original text, and by this, as Tischendorf remarks, it is evidently shown, that already in the first quarter of the second century, the gospel of St. Matthew was not only existing, and generally known in the church, but was considered to be canonical.)

*) A. Hilgenfeld, though he denies the authorship of Barnabas, calls the epistle a remarkable document of the Alexandrian Church, probably towards the end of the first century. Die Apostolischen Vaeter, p. 46.

†) The whole passage, according to the text of the Cod. Sinait. runs thus: 44 Προσέχωμεν, μήποτε, ὡς γέγραπται, πολλοὶ κλητοὶ, ὀλίγοι δὲ ἐλεκτοὶ, εὐρεθῶμεν· Of, Matth. 20, 16, 14. Katholische Literatur Zeitung, Jahrg, 9, n. 45.

) Cont. Celsum. 1, 63, o. f. de Princip. III, 2 n. 4, Exp., in Rom. n. 23.

========================================

The controversy before Sinaiticus - Credner

Matthew 20:16 (AV)

So the last shall be first, and the first last: for many be called, but few chosen.

Hippolytus and his age : or, The beginnings and prospects of Christianity Volume 1 (1854)

by

Bunsen, Christian Karl Josias, Freiherr von, 1791-1860

https://archive.org/details/a549014601bunsuoft/page/n123/mode/1up

A Gentile teacher, the author of the Epistle, preached and wrote in the spirit of Barnabas, and so the false tradition arose that it was written by Barnabas.

Of course, Barnabas does not quote the Gospel of St. John; but lie does quote "the Lord’s words" as “written down.”

The Latin text has (ch. iv.) “ sicut scriptum est: multi voeati, pauci elccti ” (Matth. xx. 16.). It appears highly uncritical to strike out, as

Credner does, these words, which are required by the sense, or to suppose, as Hilgenfeld does, that they are an inaccurate rendering of the lost Greek, “ the Lord says.” The Latin interpreter evidently understood very little Greek, but where the words are so easy he could not make a mistake. It would be still more uncritical to say that the author had before him, when making his quotations, our text of St. Matthew: there is no one passage literally the same; but the fact is that lie quotes nothing which is not found in St. Matthew (if anywhere), and two of the passages cited are neither in Mark nor Luke, and only in Matthew. It is probable therefore that he had before him one of the texts of the Palestinian Gospel, which had already at that time been stamped as St. Matthew’s, owing to the ethical arrangement of the sayings of Christ, particularly in the Sermon on the Mount. His designating (ch. xv.— end)

the Lord’s day as that of His resurrection and ascension is perfectly compatible with the closing verses of our first Gospel. We shall have to develope this point more fully in the introduction to the next age.