Steven Avery

Administrator

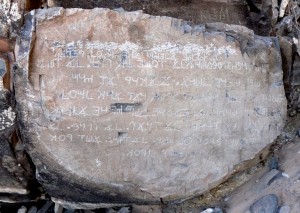

Los Lunas Decalogue Stone

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Los_Lunas_Decalogue_Stone

Cyrus Gordon (1909 – 2001), a scholar of Near Eastern languages

Barry Fell (1917 – 1994), a professor of zoology and amateur epigrapher who was an expert on starfish and sea urchins but best known for his work in the world of pseudoarchaeology. Specifically, he argued that the Americas were visited by all sorts of Old World travelers long before Columbus ever set sail. He based this on his “translations” of ancient writings found in the Americas, the majority of which were fakes, frauds, and hoaxes.

"Theories" would be fine by me -- Gordon's theory is that it's a legitimate Greco/Samaritan mezuzah. Feder's is that it's a fake. There's also a dispute over whether the caret used to indicate the insertion point for the omitted line can be ancient or if it's a relatively modern printer's mark. (Fell points out a similar mark in a Greek MS, the 4c Codex Sinaiticus if I'm not mistaken.) — Preceding unsigned comment added by HuMcCulloch (talk • contribs) 00:50, 28 February 2013 (UTC)

=======================================

The Sandia claim was discredited by Haynes and Agogino who concluded that the points found in the cave were “definitely less than 14,000 years old. ” And in the 1970s, Hibben’s claim of Folsom points at a site in Chinitna Bay, Alaska was also shown to be false.

George E. Morehouse (some spellings are Moorehouse) ( ? ), a professional geologist in the mining industry. Examined the stone in the 1980s and described it in geologic terms as well as making an age determination of the text based on its features. Morehouse wrote about it in a newsletter for a club of amateur epigraphers that lean heavily toward pseudoscience and pseudoarchaeology.

Cyrus Gordon (1909 – 2001), a scholar of Near Eastern languages and culture. He examined the Los Lunas Stone early on and came up with a hypothesis.

Barry Fell (1917 – 1994), a professor of zoology and amateur epigrapher who was an expert on starfish and sea urchins but best known for his work in the world of pseudoarchaeology. Specifically, he argued that the Americas were visited by all sorts of Old World travelers long before Columbus ever set sail. He based this on his “translations” of ancient writings found in the Americas, the majority of which were fakes, frauds, and hoaxes.

James D. Tabor (1946- ), a biblical scholar and sometime proponent of pseudoarchaeological ideas (James ossuary, Jesus tomb…) interviewed Hibbens in 1996 and believes “ancient Israelites explored and settled in the New World in the centuries before the Common Era.”

ahotcupofjoe.net

ahotcupofjoe.net

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Los_Lunas_Decalogue_Stone

Cyrus Gordon (1909 – 2001), a scholar of Near Eastern languages

Barry Fell (1917 – 1994), a professor of zoology and amateur epigrapher who was an expert on starfish and sea urchins but best known for his work in the world of pseudoarchaeology. Specifically, he argued that the Americas were visited by all sorts of Old World travelers long before Columbus ever set sail. He based this on his “translations” of ancient writings found in the Americas, the majority of which were fakes, frauds, and hoaxes.

"Theories" would be fine by me -- Gordon's theory is that it's a legitimate Greco/Samaritan mezuzah. Feder's is that it's a fake. There's also a dispute over whether the caret used to indicate the insertion point for the omitted line can be ancient or if it's a relatively modern printer's mark. (Fell points out a similar mark in a Greek MS, the 4c Codex Sinaiticus if I'm not mistaken.) — Preceding unsigned comment added by HuMcCulloch (talk • contribs) 00:50, 28 February 2013 (UTC)

=======================================

Who:

Frank Hibben (1910-2002), a professor of archaeology from the University of New Mexico was the first to make the stone public. Hibben is something of a controversy at UNM and is used as an example in classes on how not to do archaeology. Apparently Hibben wasn’t beyond tweaking the data here and there to make it look good. In the past 2-3 decades, Hibben’s research has come into question often through publications that dispute claims like that of the Sandia Cave, where Hibbens claimed to find undisturbed sediments dating to 25,000 years ago that showed human occupation.The Sandia claim was discredited by Haynes and Agogino who concluded that the points found in the cave were “definitely less than 14,000 years old. ” And in the 1970s, Hibben’s claim of Folsom points at a site in Chinitna Bay, Alaska was also shown to be false.

George E. Morehouse (some spellings are Moorehouse) ( ? ), a professional geologist in the mining industry. Examined the stone in the 1980s and described it in geologic terms as well as making an age determination of the text based on its features. Morehouse wrote about it in a newsletter for a club of amateur epigraphers that lean heavily toward pseudoscience and pseudoarchaeology.

Cyrus Gordon (1909 – 2001), a scholar of Near Eastern languages and culture. He examined the Los Lunas Stone early on and came up with a hypothesis.

Barry Fell (1917 – 1994), a professor of zoology and amateur epigrapher who was an expert on starfish and sea urchins but best known for his work in the world of pseudoarchaeology. Specifically, he argued that the Americas were visited by all sorts of Old World travelers long before Columbus ever set sail. He based this on his “translations” of ancient writings found in the Americas, the majority of which were fakes, frauds, and hoaxes.

James D. Tabor (1946- ), a biblical scholar and sometime proponent of pseudoarchaeological ideas (James ossuary, Jesus tomb…) interviewed Hibbens in 1996 and believes “ancient Israelites explored and settled in the New World in the centuries before the Common Era.”

Archaeological Fraud of the Month: Los Lunas Stone - Archaeology Review

This month we look at the Los Lunes Decalogue Stone in New Mexico which is claimed to be created by ancient Israelites.

ahotcupofjoe.net

ahotcupofjoe.net

Last edited: