Sinaiticus and P47 and more

Guiding to a Blessed End: Andrew of Caesarea and His Apocalypse Commentary in the Ancient Church

Eugenia Scarvelis Constantinou

https://books.google.com/books?id=mM7aUdl9WB4C&pg=PA184

https://dokumen.pub/guiding-to-a-bl...ary-in-the-ancient-church-978-0813221144.html

==================================

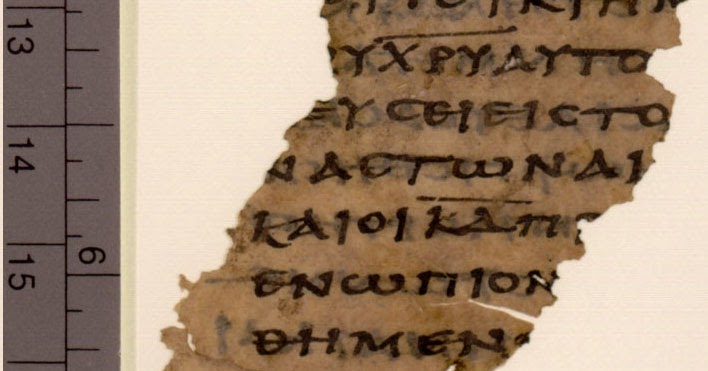

Approximately seven times more manuscripts exist of the gospels than of the Book of Revelation. Half of the manuscripts of Revelation stand alone, whereas other books of the New Testament are consistently found bound together with similar books.3 Metzger made a list of the “Greek Bibles that have survived from the Byzantine period,” and noted that the gospels exist in 2,328 copies but Revelation exists in only 287 copies, concluding: “ The lower status of the Book of Revelation in the East is indicated also by the fact that it has never been included in the official lectionary of the Greek Church, whether Byzantine or modern.”4 J. K. Elliott, citing Kurt Aland’s 1994 Liste, counted 303 manuscripts containing Revelation. He observed that only eleven uncials contain Revelation and only six papyri do, and no papyrus preserves the complete text.5 The oldest fragments are P98 in Cairo (2nd century), P47 third century (Chester Beatty), and P18 from the third or fourth century. The oldest complete text is

Sinaiticus ))אfrom the fourth century.6 David Aune lists six papyri fragments, eleven uncials and 292 minuscules7 as textual witnesses, not including patristic quotations and translations.8 Of the 292 minuscules containing Revelation, 98 are commentaries, mostly copies of Andrew.9 As can be seen by 3. Edgar J. Goodspeed, The Formation of the New Testament (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1926), 136–37. 4. Bruce Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development and Significance (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 217, citing Kurt and Barbara Aland, Der Text des Neuen Testaments (Stuttgart, 1982). 5. An uncial is a manuscript written entirely in uppercase letters. It is also known as a “majuscule.” 6. J. K. Elliot, “ The Distinctiveness of the Greek Manuscripts of the Book of Revelation,” Journal of Theological Studies, n.s. 48 (1997): 116–24, 120, citing K. Aland, ed. Kurzgefasste Liste der Griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments (Berlin, 1994). 7. A minuscule is a manuscript written with upper and lower case letters. 8. David E. Aune, Revelation, 3 vols. Word Biblical Commentary 52A, B, and C, (Nashville: Nelson Reference and Electronic, 1997), 52A: cxxxvi. Although 293 minuscules have been listed as containing Revelation, only 292 actually do. The manuscript identified as number 1277, which has been said to contain Revelation in fact does not. See David E. Aune, Revelation, 52A: cxxxix–cxl. 9. David E. Aune, Revelation, 52A: cxxxix–cxl. See David E. Aune, Revelation, 5252A: cxxvi–cxlvii for a complete listing of Revelation manuscripts. Bruce Metzger, Canon of the New Testament, 217. According to Metzger, the Book of Revelation exists in 287 manuscripts and

the figures above, apparently there is no consistent agreement on the number of existing Revelation manuscripts. A number of peculiarities also exist in the transmission of the actual text of the Apocalypse. First, the reliability presumed for ordinary text-type categories of the New Testament does not apply. Four main text-types can be identified for the Apocalypse:

(1) A C Oikoumenios, which is considered the most reliable textual “family,”10

(2) the textual tradition represented by P47 and ( אCodex Sinaiticus),

(3) the K (or “Koine”) text, which Nestle-Aland identifies as MK, and

(4)

the Andreas text type, often identified with אa (the Sinaiticus corrector) and represented in Nestle-Aland siglia as MA, or the Majority Andreas texttype.11

Approximately one-third of the total Apocalypse manuscripts are the Majority Andreas type. Therefore the commentary appears responsible for the existence of one-third more manuscripts than would have existed without the commentary, which is in itself a major contribution toward the understanding and preservation of the Apocalypse text.

The Nestle-Aland edition of the New Testament favors A C Oecumenius as the most reliable textual tradition for Revelation. This conflicts with the usual opinion regarding the reliability of these types in the rest of the New Testament, in which אis preferred and which considers A C to be inferior witnesses.12 Lachmann and Hort also regarded A as superior to the other uncials of the Apocalypse because it retains many of the Hebraisms of the author, “resulting in

wholly ungrammatical Greek, which later copyists tended either to soften or eliminate.”13 All of the text-types can be traced back at least to the fourth century. fragments. Of these, approximately 96 manuscripts contain the commentary of Andrew of Caesarea in its complete form or an abbreviated form. 10. “A” is the text type of Codex Alexandrinus and “C” is the Codex Ephraemi Syri Rescriptus. Both are fifth century uncials and their Revelation text-type resembles that of Oikoumenios. 11. J. K. Elliot, “Distinctiveness of the Greek Manuscripts,” 120. 12. J. K. Elliot, “Distinctiveness of the Greek Manuscripts,” 121. 13. R. V. G. Tasker, “ The Chester Beatty Papyrus of the Apocalypse of John,” Journal of Theological Studies 50 (1949): 60–68, 61.

However

, Hoskier completely excluded the Andreas Apocalypse manuscript family from his project and in fact expressed disdain for the Andreas manuscript tradition.16 Hoskier was particularly interested in the transmission of the Apocalypse texts “independent of Church ‘use’ and which owe their freedom from Ecclesiastical standardization to their transmission apart from the documents collected as our New Testament.”17 Hoskier qualified the term ‘use’ since the Apocalypse does not form any portion of the lectionary of the Greek East. He was referring to Apocalypse texts which were found bound in noncanonical collections, such as with collections of treatises on mystical 14. Marie-Joseph Lagrange, Introduction à l’ètude du Nouveau Testament, vol. 2, “Critique textuelle, l” Part II “La Critique rationnelle” (Paris: Gabalda, 1935), 579. 15. Herman Charles Hoskier, ed. Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse, 2 vols. (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1929), 1, x. 16. In reconstructing the Apocalypse text, Hoskier considered witnesses from Oikoumenios and from a variety of Latin sources, including Victorinus, Primasius, Cassiodorus, Apringius, Tyconius, Beatus, and pseudo-Ambrose, but did not consider Andreas, Arethas, Haymo, or Bede. He expressed a

negative opinion of the Andreas manuscript tradition: “There are so many variants in Andreas’s commentary manuscripts . . . that I have been loth (sic) to cite Andreas or Arethas positively.” Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse, 1:xxv. 17. Herman Charles Hoskier, Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse, 1: xi.

subjects or sermons. He considered those texts particularly valuable because they would presumably serve as a witness to the Apocalypse text which was less impacted by ecclesiastical concerns or interpretations. “Before the official acceptance of the Apocalypse into the Canon . . . especially by those in the East, it circulated freely from the earliest times among mystical writings, and we find it outside the New Testament included in Collections of Miscellanies.”18 Hoskier noted that more than forty Apocalypse cursives are bound up with other writings, including Hippolytus on Daniel, ascetic sermons of St. John Climacus, ascetic sermons of Ephraim, sermons of St. John Chrysostom on false teachers and on the presence of Christ, the Profession of Faith of 318 Fathers at the Council of Nicaea, the Martyrdom of the Forty Martyrs at Sebaste, and hagiographies of Sts. Nicholas, Elias, Gregory the Armenian, Simeon the Stylite, George and the Holy Archangels.19 Hoskier saw the great advantage of having two streams of testimony for the Apocalypse which “never coalesce, but at Athos today side by side we will find the Church standards and the independent texts (in collections of Miscellanies) being copied and re-copied independently.”20 Hoskier states that the double line of transmission of the Greek Apocalypse text provides a “position of superiority as regards our material compared to the other books of the New Testament, because the Apocalypse—admitted somewhat late into the Canon of Scripture— was transmitted on lines independent of ecclesiastical tenets, dogmas and traditions, and is found in the middle of many Miscellanies on mystical subjects,” providing an additional means to check other authorities.21 Hoskier believed that with the help of Sinaiticus, the large number of cursive manuscripts provide excellent witness to the third century, the time of the Decian and Diocletian persecutions. After separating 18. Herman Charles Hoskier, Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse, 1: xxvi–xxvii. 19. Herman Charles Hoskier, Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse, 1: xxvii. 20. Herman Charles Hoskier, 1: xxvii. The same point is made by David E. Aune, Revelation, 52A: cxxxvi. 21. Herman Charles Hoskier, The Complete Commentary of Oecumenius on the Apocalypse, 4.

the Greek manuscripts into their respective families, Hoskier identified “twenty or thirty separate lines of transmission, all converging back to the original source.”22 In fact and in deed this is very apparent, for we shall not find traces of a mass of copies from which our extant copies were derived, but of one frail witness standing back of them all, for it is very noticeable that in places where this original was faint or difficult to read our principle witnesses falter and labour, and guess at the word, and in these places a variety of half-a-dozen or a dozen variants has resulted, which will be found in our record.23

But since Hoskier willfully ignored the Andreas textual tradition, it was left to Josef Schmid to provide the definitive work on the text of the Apocalypse in the mid-twentieth century.24 After exhaustively examining all of the Apocalypse manuscripts, Schmid identified the main Apocalypse text types as

(1) the Andreas text type or—Αν

(2) the Koine or K,

(3) A C Oikoumenios, and,

(4) the group which includes P47, Sinaiticus and Origen.

Schmid’s findings are over fifty years old and need to be updated and reconsidered, but his work on the text of Revelation remains unparalleled. As part of his work on the Apocalypse text, Schmid also created and published the critical text of the Commentary on the Apocalypse by Andrew of Caesarea. Schmid’s main concern in editing the commentary of Andrew of Caesarea had been to determine one of the chief text types for Revelation, that of Andrew, which he designated “Αν” for Ἀνδρέας. He wanted to determine whether an early text form of the Apocalypse could be accessed by an examination of the Andreas text type.25 Schmid determined that all of the Αν texts go back to one original, either the auto

22. Herman Charles Hoskier, Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse, 1: xx.

23. Herman Charles Hoskier, Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse, 1: xvi.

24. Josef Schmid, Studien zur Geschichte des griechischen Apokalypse-Textes, 3 parts (München: Karl Zink Verlag, 1955–56). Part 1 Der Apokalypse-Kommentar des Andreas von Kaisareia Text (1955), Part 2 Die alten Stämme (1955), and Part 3 Historische Abteilung Ergänzungsband, Einleitung, (1956).

25. Georg Maldfeld, “Zur Geschichte des griechischen Apokalypse-Textes,” Theologische Zeitschrift 14 (1958): 47–52, 48.

graph of the Andreas commentary or a copy of it.26 However, he also concluded that the Revelation text in the original Andreas commentary is older than the commentary itself, going back to a previously worked over text,27 and can be found in the Sinaiticus corrector אa.28 After analyzing the Andreas manuscripts along with the other Apocalypse manuscript types, Schmid rejected Von Soden’s assertion that Andrew himself had created the Andreas text-type out of a mixture of several manuscripts.29 Schmid supported his conclusion not only by his analysis of the relationship between variants found in the texts, but also from the statements of Andrew in the commentary, which indicate that Andrew was following an existing text, as well as his comment regarding the need to respect the text regardless of any violations of proper Attic syntax.30 The K text exists in a number of archetypes from approximately the ninth century, and can be found in a number of related families. P47 and Origen are witnesses for the text in the third century and stand in an independent relationship to each other. Where they agree, the presumption is that they preserve a reading older than 200 C.E. They also seem to represent an Egyptian tradition and are associated with Coptic versions. The A C Oikoumenios group contains the best manuscript tradition. The most reliable by far is A, which, although it is from the fifth century, is a better text than Origen’s which is two hundred years older.31 Schmid concluded that the history of the Apocalypse text can only be traced back to about 200 C.E., and that most of the variants occurred in the first one hundred years of the transmission of the text.32 26. Josef Schmid, Einleitung, 127. G. D. Kilpatrick, “Professor J. Schmid on the Greek Text of the Apocalypse,” Vigiliae christianae 13 (1959): 1–13, 3. In the terminology of manuscripts and textual criticism, an “autograph” is simply the “original” document written by the author himself. 27. Georg Maldfeld, “Zur Geschichte,” 49. 28. G. D. Kilpatrick, “Professor J. Schmid on the Greek Text,” 3. 29. Josef Schmid, Einleitung, 125. 30. Josef Schmid, 125. See Andrew, Chap. 72, Comm. 241–42. 31. G. D. Kilpatrick, “Professor J. Schmid on the Greek Text,” 4–5. 32. G. D. Kilpatrick, “Professor J. Schmid on the Greek Text,” 5.

JUMP AHEAD

=====================

R. V. G. Tasker, discussing the Chester Beatty papyrus which contains one of the oldest fragments of the Apocalypse (P47), concurred: “It is generally recognized that the text of the Apocalypse, a book which gave some offence in certain quarters of the Greek-speaking Church in the second century, was subject from an early date to a series of attempts to improve the very Hebraic character of its Greek.”35

Schmid observed that the text used by Andrew was older than even the text which influenced the Codex Sinaiticus and that the Koine text and Andreas type are closely related.36 However, their transmission was quite different.

=====================

JUMP AHEAD

Dr. Hernández continues to make important contributions toward our understanding of Apocalypse interpretation by the study of textual variants.49 46. Josef Schmid, Einleitung, 129. 47. Josef Schmid, Einleitung, 129. 48. Juan Hernández Jr., “Codex Sinaiticus: An Early Christian Commentary on the Apocalypse?” From Parchment to Pixels: Studies in the Codex Sinaiticus, ed. David C. Parker and Scot McKendrik (London: British Library, forthcoming). See also his “A Scribal Solution to a Problematic Measurement in the Apocalypse,” New Testament Studies 56 (2010): 273–78, and “Andrew of Caesarea and His Reading of Revelation: Catechesis and Paranesis,” Die Johannesapokalypse: Kontexte und Konzepte, ed. Jörg Frey James A. Kelhoffer, and Franz Tóth (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012). 49. Juan Hernández Jr., Scribal Habits and Theological Influences in the Apocalypse: The Singular Readings of Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus and Ephraemi (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006).

=====================

=====================

ing their resemblance to each other, being “eager to point out their complete identity of content, closely connected to one another like a chain.”80

80. Andrew, Chap. 67, Comm. 230. 81. Andrew, Chap. 67, Comm. 230, referring to Rev. 21:21, John 10:9, John 14:6 and Matt. 13:46 respectively. 82. This is a significant textual variation. This reading (ποιοῦντες τὰς ἐντολὰς αὐτοῦ) is found in the Majority Andreas text, as well as Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus. The preferred reading is “Blessed are they who wash their robes” (πλύνοντες τὰς στολὰς αὐτῶν), which is also the reading in Oikoumenios. Metzger believes the scribal variation occurred because of the similarity in sound and because elsewhere (Rev. 12:17 and 14:12) the author writes of keeping the commandments (τηροῦντες τὰς ἐντολάς). Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary, 765. 83. Andrew, Chap. 71, Comm. 239–40. 84. Andrew, Chap. 68, Comm. 233, commenting on Rev. 22:2, citing Is. 61:2.

More on Sinaiticus P47 etc see Greek manuscripts of Revelation

==================================

==================================