p. 253-255

Magdalen College fragments

Fabricating a Second-Century Codex

253

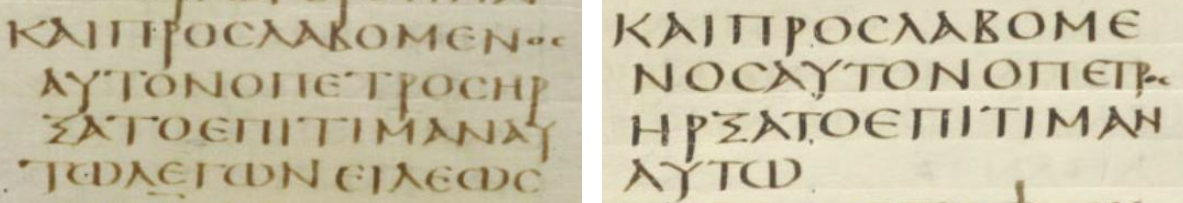

From Codex to Icon: Popular Media Interest and Two More Gospels Yet, so far this story is pretty mundane. As we have seen with the Beatty Biblical Papyri and the Bodmer Papyri, it is not unusual for parts of the same codex to be divided among different holding institutions. It was not until the mid-1990s that these fragments became truly exceptional. On Christmas Eve 1994, the Times ran a frontpage story carrying the title “Oxford papyrus is eyewitness record of the life of Christ.” The Oxford papyrus in question was the fragmentary leaf of Matthew at Magdalen College. Nearly two full pages in the Times gave voice to the case of Carsten Thiede (1952–2004), who argued that the Matthew fragments dated not to the late second century, as Roberts had claimed, but to “the mid-first century.”9 The Christmas Eve news story appeared in anticipation of an academic article to be published by Thiede in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik in 1995.10 This article spelled out Thiede’s ideas more fully. First, he argued that the Paris fragments of Luke were part of a different book that was copied “considerably later (by up to one- hundred years).” The fragments of Matthew from Oxford and Barcelona were then said to date from “the first century, perhaps (though not necessarily) predating AD 70.” Thiede’s “argument” (I use the term loosely) for this new date was purely paleographic, based on asserted similarities with Greek writings from Nahal Hever and Qumran in Palestine and Herculaneum in Italy. Thiede’s article drew swift rebuttals from the academic community, with a subsequent issue of Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik publishing a thorough, point-by-point refutation by Klaus Wachtel.11 Undaunted, and indeed buoyed by the ongoing publicity, Thiede and the author of the original column in the Times copublished a popular book reasserting and elaborating Thiede’s claims and attacking his critics.12 Thiede’s proposals again failed to persuade any experts, but the tactic of making his case in the media and the popular press drew worldwide attention to his claims.13 Thiede’s ideas were featured in the New York Times, on the cover of Der Spiegel, and in many other prominent media outlets.14 In the following year, another article in a major biblical studies journal kept the spotlight on these fragments. The papyrologist The-

254

Fabricating a Second-Century Codex

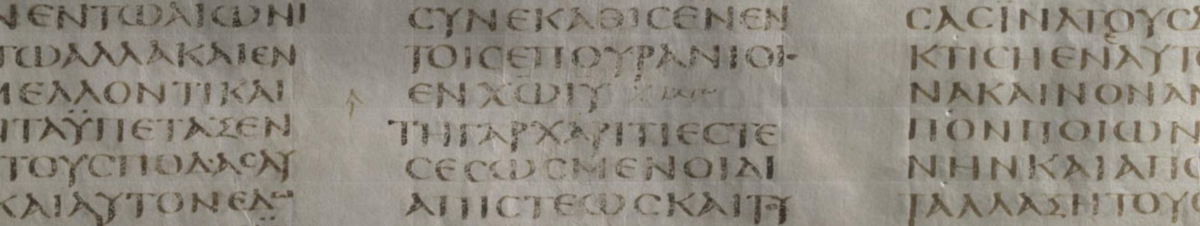

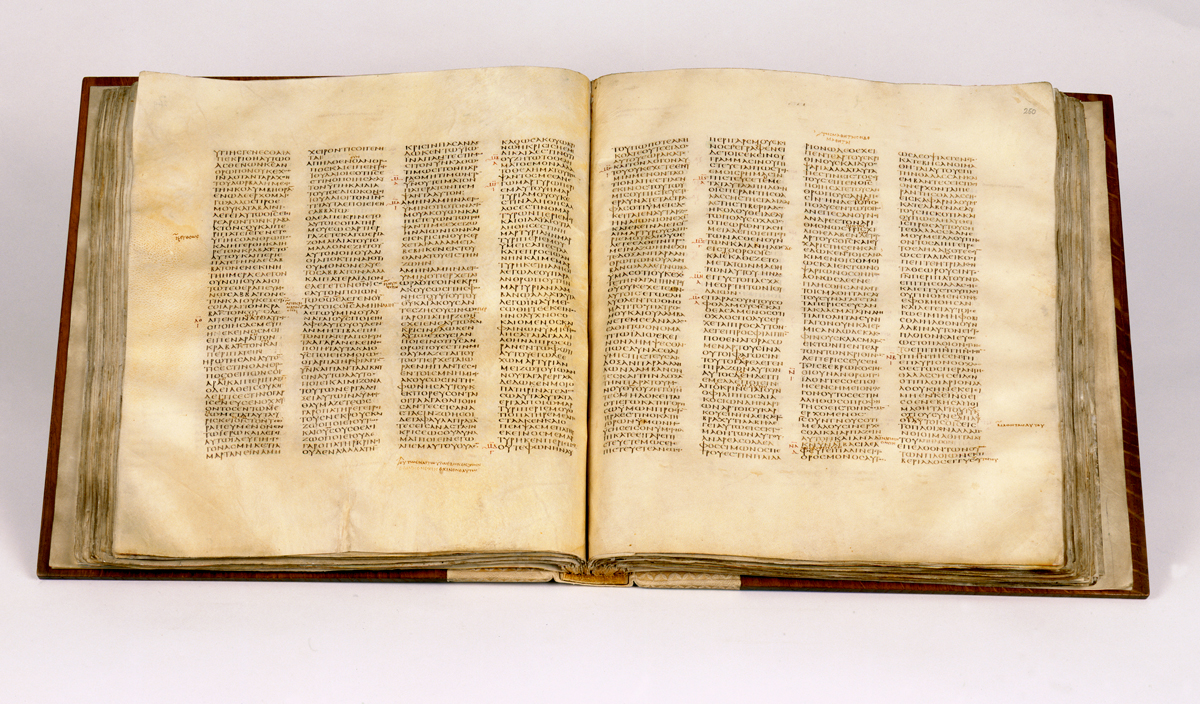

odore Skeat (1907–2003) laid out a thesis that is in some ways just as astonishing as the claims made by Thiede. Skeat was convinced that these fragments were once part of a codex that contained all four gospels.15 Thus, like Roberts, Skeat believed that all the fragments of Matthew and the fragments of Luke must have come from the same codex. But Skeat went even further. In a long and detailed discussion, he tried to extrapolate numbers of letters that would have appeared on individual pages of the Matthew fragments to demonstrate that the codex could not have contained only Matthew and Luke and that it must have been a single-quire construction. According to Skeat, the codex must have contained something else between the gospels of Matthew and Luke, and there was no doubt about what that “something else” must be: “We come to the conclusion that another Gospel or Gospels must have intervened at this point; and since a codex containing three gospels is unthinkable, the only possible conclusion is that the manuscript originally contained all four Gospels.”16 Skeat was not deterred by the fact that codices with three gospels are known, as are codices that mix gospels and other literature.17 Skeat also offered the fullest paleographic discussion of the fragments and made a vigorous argument that this four-gospel codex was datable to the second century. At the same time, however, he observed that “the general appearance of the script” could be described in the very terms used to characterize the writing of Codex Sinaiticus, which is generally thought to have been copied in the middle of the fourth century.18 Skeat also spent several paragraphs puzzling over how Frederic Kenyon could have assigned the Luke fragments to the fourth century but the Philo codex to the third century.19 This point is important, and I return to it shortly. Later that same year, our fragments of Matthew and Luke featured prominently in another article in the same journal. In the printed version of his presidential address to the Society for New Testament Studies, Graham Stanton, Lady Margaret’s Professor of Divinity at Cambridge, fully accepted Skeat’s arguments and pushed them still further. He wrote: “Skeat has now shown beyond reasonable doubt that 𝔓64+𝔓67+𝔓4 are from the same single-quire codex, probably our earliest four-Gospel codex which may date from the

Fabricating a Second-Century Codex

255

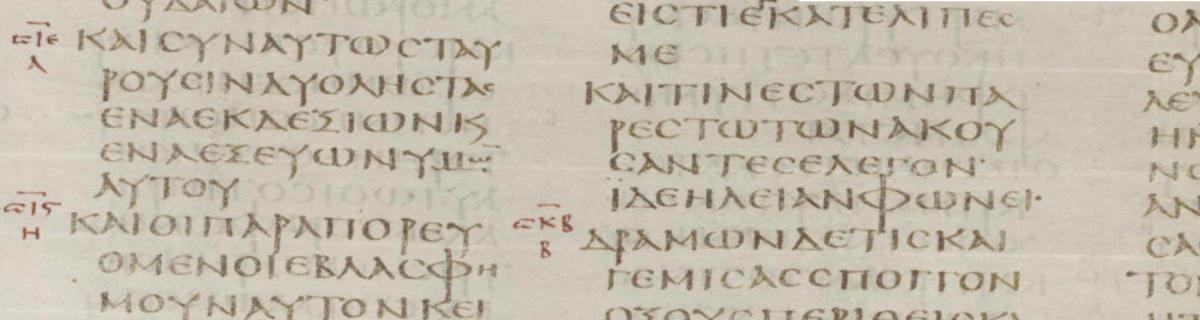

late second century. . . . The codex was planned and executed meticulously: the skill of the scribe in constructing it is most impressive. . . . This codex does not look at all like an experiment by a scribe working out ways to include four gospels in one codex: it certainly had predecessors much earlier in the second century.”20 For Stanton, then, we have not just one, but multiple luxury codices containing all four canonical gospels, and they were circulating not just at the end of the second century, but much earlier in the century as well! We have come a long way from five small fragments of Matthew’s gospel and a few damaged leaves of Luke. The papers by Skeat and Stanton provoked several responses. The two most important appeared in New Testament Studies. Peter Head addressed Skeat’s mathematical calculations of letters per page and demonstrated that because of the fragmentary nature of the evidence, Skeat could not possibly achieve the precision he claimed.21 Shortly after that, Scott Charlesworth, in a very detailed analysis, pointed out that Skeat’s argument that the fragments all came from one single-quire codex had neglected the one crucial type of evidence that could be almost decisive for such an argument—the directions of the fibers of the individual leaves. It turns out that on some of the fragments of Matthew, the horizontal fibers precede the vertical, and on others, the vertical precede the horizontal. So, for example, one of the Barcelona fragments contains Matt 3:9 written on the vertical fibers and Matt 3:15 on its reverse written along the horizontal fibers, but the other fragment contains Matt 5:20–22 written along the horizontal fibers and on its reverse Matt 5:25–28 written against the vertical fibers. Thus, the center of a quire most likely intervened between these fragments. The same alternating pattern is true of the leaves of Luke, which shows that both the Matthew fragments and the Luke fragments probably came from multiquire codices.22 So, Skeat’s four-gospel, single-quire codex theory of these fragments has not carried the day, but the question of whether the Matthew and the Luke fragments might come from the same multi-quire codex remains open.23 And there is still broad agreement that the Luke fragments (and perhaps the Matthew fragments) come from a known archaeological context (the house in Koptos) and have a secure terminus ante quem in that they were used to construct the

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com

brentnongbri.com