RGA - p. 60

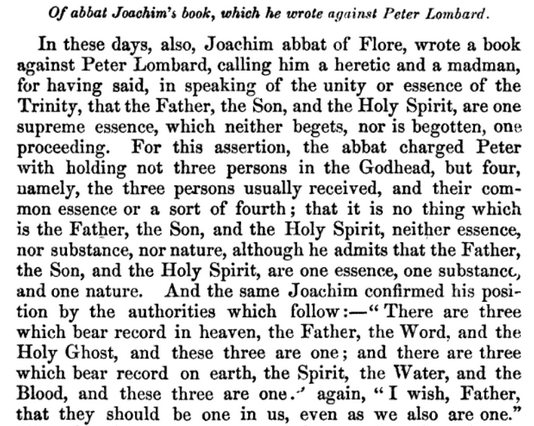

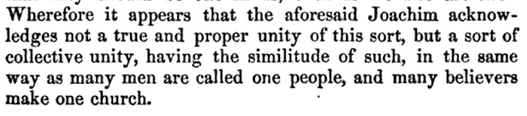

The Acts of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) contain an interesting detail of some relevance to the transmission of the comma. The first book of the Council’s Acts deals with matters of doctrine, beginning with the condemnation of certain criticisms of the lost treatise On the unity or essence of the Trinity (De unitate seu essentia Trinitatis) by Joachim of Fiore (c. 1135-1202). Joachim had accused Peter Lombard (Sententiæ I.1, dist. 5) of introducing a fourth element to the Trinity, an essence shared by all three persons (communis essentia), which is not ingenerated, generated or proceeding. Joachim had suggested rather that we ought to think of the Trinity in terms of a collectivity of three separate beings. His argument ran as follows: Jesus had prayed that his followers—that is, the church—might be one, just as he and the Father are one (Jn 17:22). It is clear that the members of the church are not one thing, but still may be thought of as one in the sense of belonging to a collectivity. Likewise, when John says that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit testifying in heaven are one, he is clearly not attributing to them a unity of essence, since the following verse asserts that the Spirit, the water and the blood are also one, and this latter assertion can only refer to an agreement of testimony rather than a unity of essence.102 Joachim’s suggestion that the Trinity is merely a collectivity rather than an indissoluble union of three eternally consubstantial persons earned him the Council’s condemnation.

1960, 142, 233, 375.

102 The text of the Lateran Council’s decision is in Denzinger, 2001, 359-362, §§ 803-808, esp. 803:

“Ad hanc autem suam sententiam adstruendam illud potissimum verbum inducit, quod

Christus de fidelibus inquit in Evangelio: Volo, pater, ut sint unum in nobis, sicut et nos unus

sumus, ut sint consummati in unum. Non enim, ut ait, fideles Christi sunt unum, id est quædam

una res, quæ communis sit omnibus, sed hoc modo sunt unum, id est una Ecclesia, propter

catholicæ fidei unitatem, et tandem unum regnum, propter unionem indissolubilis caritatis,

quemadmodum in canonica Ioannis Apostoli epistola legitur: Quia tres sunt, qui testimonium

dant in cælo, Pater, et Filius, et Spiritus Sanctus: et hi tres unum sunt, statimque subiungitur: Et

tres sunt, qui testimonium dant in terra: Spiritus, aqua et sanguis: et hi tres unum sunt, sicut in

quibusdam codicibus invenitur.”

Joachim’s position on the comma has certain similarities to that of Ambrosius Autpertus († 784), who said that since the three that bear witness in heaven are one, so their testimony must also be one; see his Expositio in Apocalypsin, CCCM 27:42-43:

“De quo et subditur: QVI EST TESTIS FIDELIS, PRIMOGENITVS MORTVORVM, ET PRINCEPS REGVM TERRÆ. Ea locutionis regula, quam supra præmisimus, solus hoc [43] loco Filius testis uocatur fidelis, cum et Pater et Spiritus Sanctus simul testimonium fidele perhibeant de ipsis, sicut

scriptum est: Tres sunt qui testimonium dicunt de cælo, Pater et Verbum et Spiritus Sanctus, et hi tres unum sunt. Sciendum autem, quia sicut hi tres unum sunt, sic horum testimonium unum esse cognoscitur, quamquam alterius testimonio alter insinuetur.” Ambrosius cites the comma

again, CCCM 27:182. See also Garin, 2008, 1:25-26.

RGA - p. 63

Ia.29.4 that Augustine had cited the comma in his De Trinitate, apparently confusing Augustine with Peter Lombard, Sentences

1.25.)108 In his remarks on the Lateran Council’s condemnation of Joachim’s proposition, Aquinas defends the canonicity of the comma. ... According to Aquinas, Joachim’s interpretation of the unity of the heavenly witnesses as one of love and testimony rather than one of essence was a perversion of its true sense. ... For Aquinas it was clear that Joachim had fallen into the error of the Arians, and had therefore rightly been condemned by the Council.109

108 Aquinas, 1964-1981, VI.56-57; Meehan, 1986, 8.

109 (Aquinas Latin)

RGA - p. 65

One of the issues discussed at the Fourth Lateran Council was a rapprochement between the Roman and Byzantine churches; as part of this process, the Acts of the Council were translated into Greek. The section in which Joachim’s propositions are condemned is the first documented occurrence of the comma in Greek.113

113 The passage from the Greek translation of the Acta is given in Martin, 1717, 138; Martin, 1722, 170; Horne, 1821, 4:505; Seiler, 1835, 616: ὅτι τρεῖς εἰσιν οἱ μαρτυροῦντες ἐν οὐρανῷ, ὁ πατήρ, λόγος, καὶ πνεῦμα ἅγιον, καὶ τοὕτοι [sc. οὗτοι] οἱ τρεῖς ἕν εἰσιν. This reading resembles

that in Codex Montfortianus (except for the omission of τῷ before οὐρανῷ and the insertion of the article ὁ, which apparently does duty for all three persons) so closely that we might suspect that the scribe of Montfortianus had consulted this document. There is a fifteenth-century

Greek ms of the Acta of the Lateran Council in the Bodleian Library, but it is one of the Codices Barocciani, brought from Venice and given to the University in 1629 by Lord Pembroke (Cod. Barocc. 71, 84-87); see Coxe, 1853, 114

RGA - p. 84

(Surely Erasmus was not unaware of Aquinas’ condemnation of Joachim’s interpretation of these passages.)

RGA - p. 88

The new marginal note consists of a condensed extract from Thomas Aquinas’ commentary on the decision taken at the Fourth Lateran Council to condemn Joachim of Fiore’s position on the Trinity.35

The the Screech error on the Complutensian

RGA - p. 152-153

In Jn 10:30, Servetus notes that the neuter unum refers to unanimity and

concord of wills, not numerical sigularity. He approves of those early Christian

theologians who spoke of one ousia, that is, of the power given by the Father to

the Son, but he considered that the later coinages homousion, hypostasis and

persona arose from a distortion of the original meaning of ousia.7 When Servetus

comes to interpret the comma, his interpretation is surprisingly close to that of

Joachim of Fiore, as outlined and condemned by Aquinas in his exposition of the

decretal of the Lateran Council. Like Joachim, Servetus considered that the unity

of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit was one of testimony only, an interpretation

he also finds in the Glossa Ordinaria.8 Servetus would restate some of the same

arguments in his Christianismi restitutio (1553): that the one deity which is in the

Father was communicated to the Son, the only person in whom divinity was

communicated in an unmediated and corporeal way. From him the Holy and

substantial Spirit [halitus] was given to others. Turning to the matter of the

comma, Servetus argues that the three heavenly witnesses all bear witness to the

unity of the deity, and the three earthly witnesses—the water, blood and spirit

that issue from the dying Jesus—show that he was not an incoporeal being, but

that this man was really the Son of God. It is alway’s John’s intention, Servetus

emphasises, to underline Jesus’ status as Son of God.9

Grantley BCEME error, on Joachim, may only have RGA

BCEME p. 35

The new marginal note, drawn from Thomas Aquinas’ commentary on the condemnation of Joachim of Fiore’s position on the Trinity at the Fourth Lateran Council, has two functions. First, it gives an authoritative theological justification for the omission of the phrase καὶ οἱ τρεῖς εἰς τὸ ἕν εἰσιν at the end of v. 8 in the Complutensian edition. More importantly, it shows, on the authority of Aquinas himself, that Erasmus’ omission of the comma from his edition and his inclusion of the last phrase of v. 8 betrayed a hint of Arianism.

BCEME - p. 96

Biandrata declared that the first Christians had no doctrine of the Trinity, a conclusion reached earlier by Joachim of Fiore, Erasmus, Servet and Bernardino Ochino, a prominent Italian Franciscan who subsequently converted to Calvinism and then to Antitrinitarianism.